Hate Bias Discrimination

The University of New Orleans strives to develop a diverse and inclusive community that ensures equal access, opportunity, participation, free inquiry, and representation for all. However, on occasion, bias-related incidents and behaviors of community members can have a negative impact on others. Bias-related incidents and/or hate crimes impede our ability to become communities of inclusive excellence. These exchanges reduce the opportunities for a respectful conversation to share our perspectives, experiences, and ideas. UNO takes these incidents and behaviors seriously. If you believe a bias-related incident has occurred, you may report it here https://uno.guardianconduct.com/incident-reporting

The Bias-Incident Protocol is not a disciplinary body and will not investigate, adjudicate or take the place of other University processes or services; rather, the aim is to complement and work with campus entities to connect impacted parties and communities with appropriate support and resources.

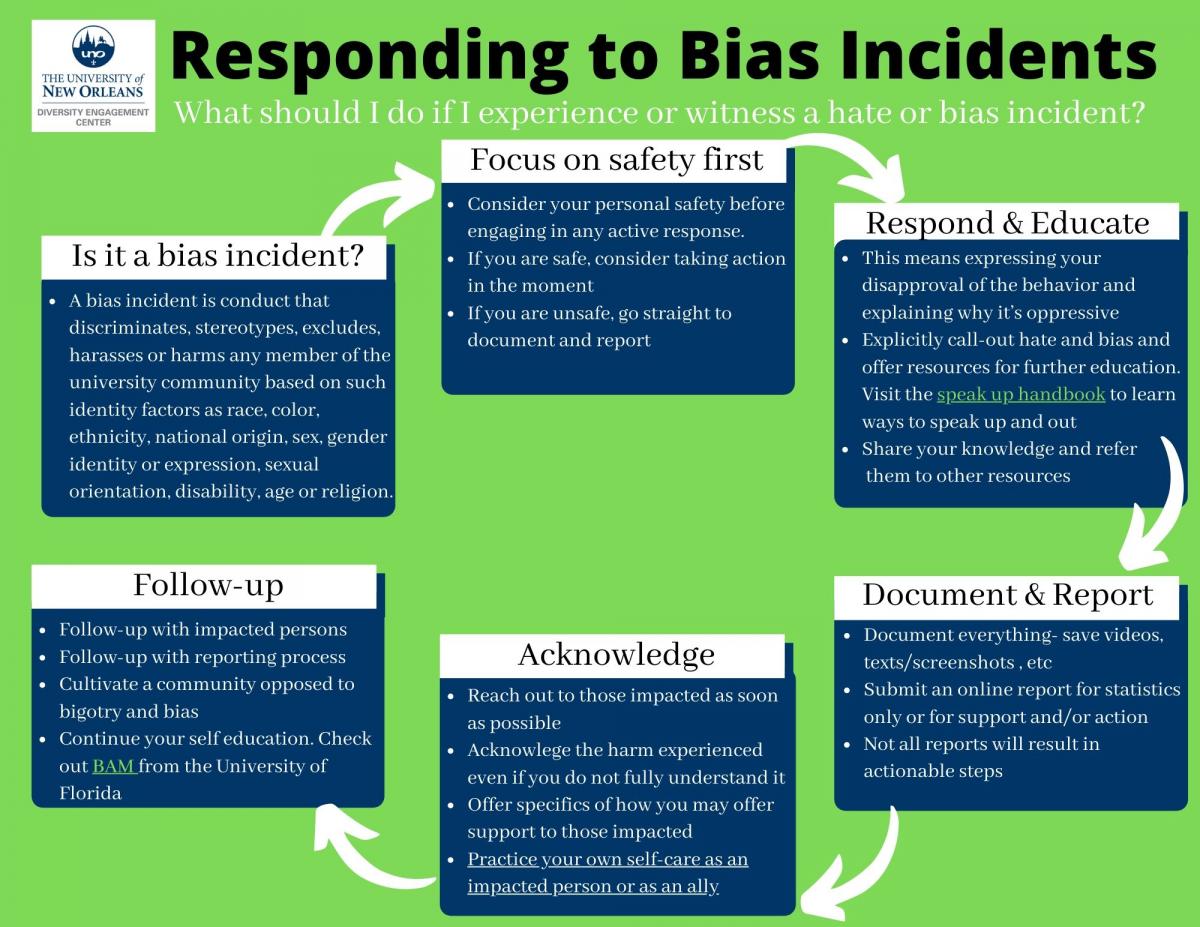

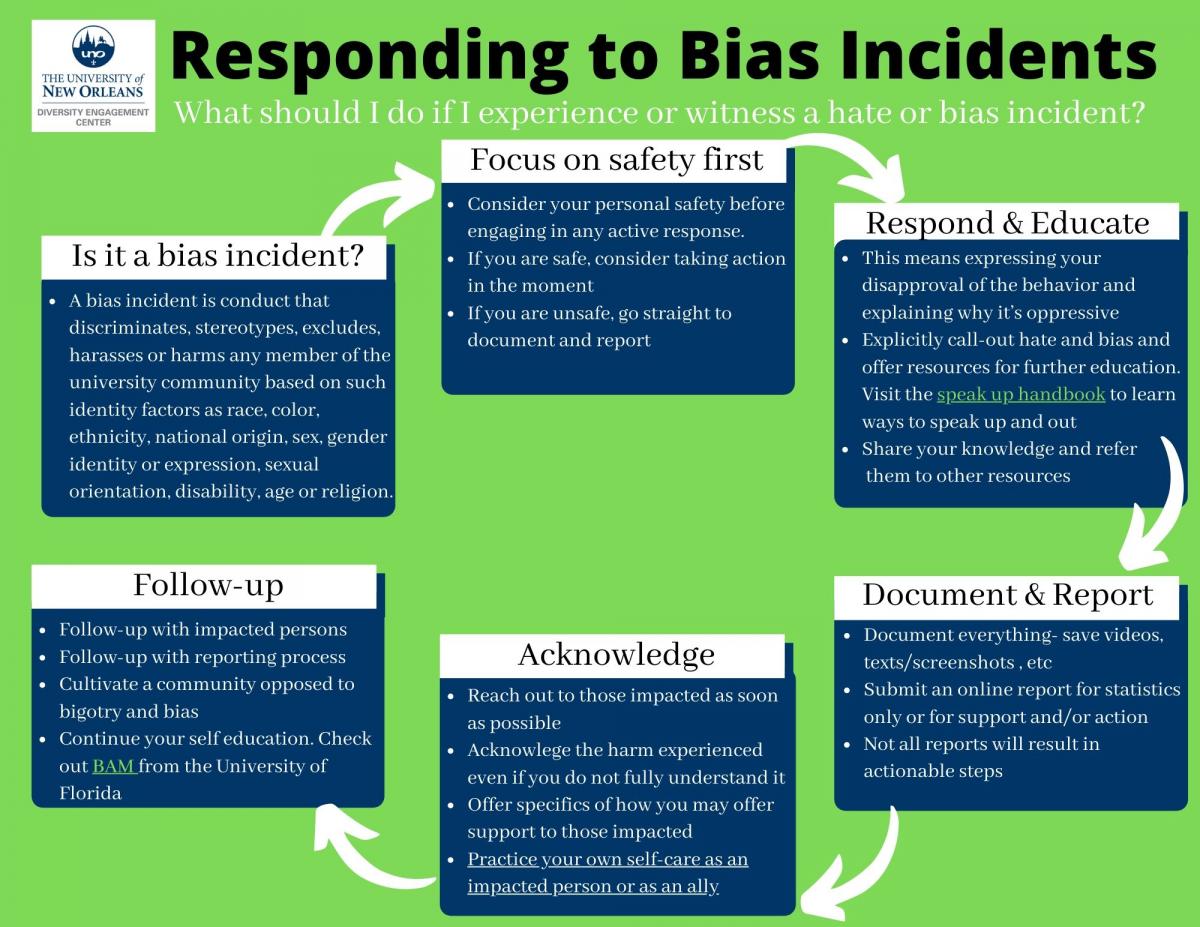

Steps for intervention

Public harassment or hate/bias can occur unexpectedly in virtually any location. It may be on a bus, at school, at a shopping center, in a park, on social media, or at/in any number of other public spaces. The unpredictable nature of such harassment can leave us feeling unprepared when an incident occurs.

1. Know What Public Harassment Looks Like. Understanding that harassment is happening – and why it’s happening – is the first step toward effective intervention. Recognize that harassment exists on a spectrum of actions ranging from hurtful comments and gestures to violence. The type of bigotry fueling the harassment can also run the gamut. Racism, sexism, ageism, classism, xenophobia, homophobia, or religious discrimination are a few examples.

2. Look at yourself

3. Recognize Your Blocks, Or Reasons Why You May Not Intervene. We all have such blocks. Sometimes we’re scared. Other times, we may feel we can’t make a difference – even if we act.

4. When An Incident Occurs, Choose One Of “The Five D’s Of Bystander Intervention.” Each of the Ds offers a clear path of action. They include the following: Direct, Distract, Delegate, Delay, Document

a1. Direct: “That’s not cool.” Directly address the incident or harasser by stating that what’s happening is inappropriate or disrespectful. Direct intervention has many risks; exercise it with caution and assess the situation for your safety first;

a2. Say something indirectly

b. Distract: “Hey, what time is it?” Use distraction to stop the incident. The goal is to interrupt the incident by engaging the person being targeted and ignoring the harasser;

c. Delegate: “Can I get your help over here?” Ask for help from a third party like a manager in the store, a driver on the bus, or a faculty or staff member on campus;

d. Delay: “Are you OK?” If you can’t take action in the moment, you can make a difference afterward by checking on the people targeted. Ask how you can help and share resources for advocacy groups and reporting;

e. Document: “I’m recording this.” It can be really helpful to record an incident as it happens, but there are a number of things to keep in mind to safely and responsibly document harassment. Assess the situation. Is anyone helping the person being harassed? If not, use one of the four steps above. If someone else is already helping, assess your own safety. If you are safe, start recording and keep the following tips in mind:

adapted from the Southern Poverty Law Center

Below are additions sets of questions or phrases that you can use when you encounter or witness hurtful, harmful, and hateful behavior from step 4a1.

INQUIRE: Ask the speaker to elaborate. This will give you more information about where s/he is coming from, and may also help the speaker to become aware of what s/he is saying.

KEY PHRASES:

PARAPHRASE/REFLECT: Reflecting in one’s own words the essence of what the speaker has said. Paraphrasing demonstrates understanding and reduces the defensiveness of both you and the speaker. Restate briefly in your own words, rather than simply parroting the speaker. Reflect both content and feeling whenever possible. This is also helpful to the listener to understand that what they communicated perhaps was not what they intended and they can clarify.

KEY PHRASES:

REFRAME: Create a different way to look at a situation.

KEY PHRASES:

USE IMPACT AND “I” STATEMENTS: A clear, nonthreatening way to directly address these issues is to focus on oneself rather than on the person. It communicates the impact of a situation while avoiding blaming or accusing the other and reduces defensiveness.

KEY PHRASE:

Adapted from Kenney, G. (2014). Interrupting Microaggressions, College of the Holy Cross, Diver

If individuals do decide to take action, they must contemplate how to react. First, they can approach the situation in a passive-aggressive way. For instance, perhaps the victims make a joke or a sarcastic comment as a way of communicating that they are upset or annoyed. Perhaps the target responds by rolling their eyes or sighing. Or, they do nothing at that moment and decide to talk to others about it first, in the hopes that it will get back to the responsible person. Second, targets can react in a proactive way. This might be effective when the target or witness simply does not have the energy to engage the responsible person in a discussion. Sometimes individuals who experience microaggressions regularly may feel so agitated that they just want to yell back. For some individuals, an active response may be a therapeutic way of releasing years of accumulated anger and frustration. Finally, an individual may act in an assertive way. This may include calmly addressing the responsible person about how it made them feel. This may consist of educating the responsible person, describing what was offensive/harmful about the microaggression. Oftentimes the responsible person will become defensive, which may lead to further microaggressions. It may be important to use “I” statements (e.g., “I felt hurt when you said that.”), instead of attacking statements (e.g., “You’re a racist!”). It also may be important to address the behavior and not the person. What this means is that instead of calling the person “a racist,” it might be best to say that the behavior they engaged in impacted me in this way or impacts this community in that way and is offensive for these reasons.

This Interrupting Microaggressions Table provides an outline of how certain words and phrases communicate, perhaps an unintended message to the receiver as well as statements and phrases witnesses or targets may use to engage with responsible persons when microaggressive behavior occurs.

adapted from: https://advancingjustice-la.org/sites/default/files/ELAMICRO%20A_Guide_to_Responding_to_Microaggressions.pdf

When faced with social injustices, bias incidents, and controversial speakers, it is extremely difficult to cope and know what to do. Feeling overwhelmed with the current socio-political state, experiencing discrimination, or being impacted by contentious people or policies increases stress which remains correlated to negative mental health outcomes. During these times, it remains imperative that we take care of ourselves, take care of loved ones, and take care of our campus community.

It is essential for us to take action, engage in intentional self-care– to an extent and at the level you are ready to do so. By doing so, we support our personal and community holistic health. By reflecting, engaging, and taking action, we are making positive contributions to our mental and emotional health. Please remember that speaking up and acting in ways that are aligned with your values can take many different forms. And each step counts; small acts of self-care, and community-care make a big difference. Below are some suggestions and resources for actively coping with social injustices and hatred.

By educating ourselves and staying committed to building a community of care, we can make strides in creating a more connected and inclusive campus.

Personal

Reflect on who you are. We all have biased thoughts and beliefs. Look into your own biases and stereotypes. Explore your intersecting identities. Recognize where your privilege lies. Read about allyship and even better how to be an accomplice. Take BAM! Best Allyship Movement, an online training from the University of Florida that walks you through these steps.

Educate yourself about social injustices and speech that marginalizes communities that you are unfamiliar with or want to revisit. Be clear about what is unacceptable to you in their rhetoric. Sign-up for workshops, seminars, and discussions through the Diversity Engagement Center or wherever you can find them.

See the impact. Recognize when a bias incident or hate crime happens, understand how it hurts us all, leaving the community unsafe and on-guard. If you do not understand how communities or individuals have been harmed go back to the educate yourself step. Don’t rely on those in the community to educate you as they may be emotionally taxed and unable to give you the best they have to offer.

SPEAK UP and SPEAK OUT against injustice. Do not merely be a bystander. Understand when and how to use your voice to be an activist or ally for yourself and others. Consider using the methods and strategies outlined here. Consider the 4 D’s of Bystander Intervention: Direct, Distract, Delegate, and Delay.

Allow your emotions to be. It is normal to have a wide range of emotions and reactions. Own your feelings. Recognize that they are normal and valid. Find a safe outlet to express your emotions. When others approach you remember that they do not know your emotional state and while it may be the 75th time someone has asked you the same question it is the first time that person has asked. On the flip side When approaching others remember they may be in a fragile or sensitive state and while it is your first time asking them a question it may be the 75th time someone asked them a question.

Set boundaries. Stay away from people and places that make you uncomfortable. Take breaks away from media and social media. Engage in and disengage from conversations as you need. Assert your needs and own your readiness especially if you feel judged for not being or acting a certain way. Listen to your instincts and remember that cultural mistrust -lack of trust in the mainstream culture due to experienced and historical oppression- has been a survival strategy for marginalized groups.

Tap into your resources. Connect with others who “affirm your humanity.” Join a student club/organization whose mission connects with your values and ideals. Get support from allies, accomplices, groups, and experts on campus including the Diversity Engagement Center and the International Center. When ready, make new connections by reaching out to people outside your own comfort zone.

Engage in conversations. Dialogue with others about uncomfortable topics such as issues of race, class, gender identity, religion and so forth. Educate others -- when you have the emotional capacity to do so -- about the negative impact of hate, bias, and discrimination. Share stories of acceptance, respect and unity. If comfortable, share your own personal experiences. Promote taking action.

Support your community. Engage in volunteering work. Show those who are targeted by biased messages that you are with them in solidarity. If you know about a bias incident or hate crime, show the target that you care by checking-in with, being an active bystander, and reporting the incident (if the target wishes).

Work to enhance the connection/unity within your community whether it is your hall, your student club/organization, or your department. Collaborate with a diverse set of student clubs/organizations and campus departments. Organize events that celebrate and educate about cultural differences, heritages, and lived experiences.

Work with leaders including deans, presidents, student leaders, residential advisors, campus police, faculty, university officials, and politicians. Encourage them to publicly address causes of hate and the wide-spread negative effect on the campus community.

Work with media. Ask for nuanced and thoughtful news coverage. Invite journalists to share stories that communicate the impact of hate at individual and community levels.

Find ways to speak up. Demonstrate, protest and show your opposition through diverse and positive means. Consider finding creative ways to be heard without giving controversial speakers the attention they seek.

Adapted from the University of Michigan